MIPS Processor (Technical)

This is a technical description of my MIPS processor project. To read from a non-technical perspective, check out MIPS Processor (Overview).

About

This write-up showcases an in depth exploration of three different processor designs: a single-cycle design, a software-scheduled pipeline, and a hardware-scheduled pipeline. Each processor underwent careful design, implementation, and performance analysis, highlighting the practical applications and tradeoffs involved in computer architecture.

The primary objective was to create functioning MIPS assembly processors with schematic designs, control spreadsheets, and VHDL implementation. The single-cycle processor, built first, introduced me to novel concepts in computer architecture design. The design, components, and tests were all created from scratch, and subsequent processors based on the single-cycle design aimed to optimize performance through pipeline strategies and hazard mitigation.

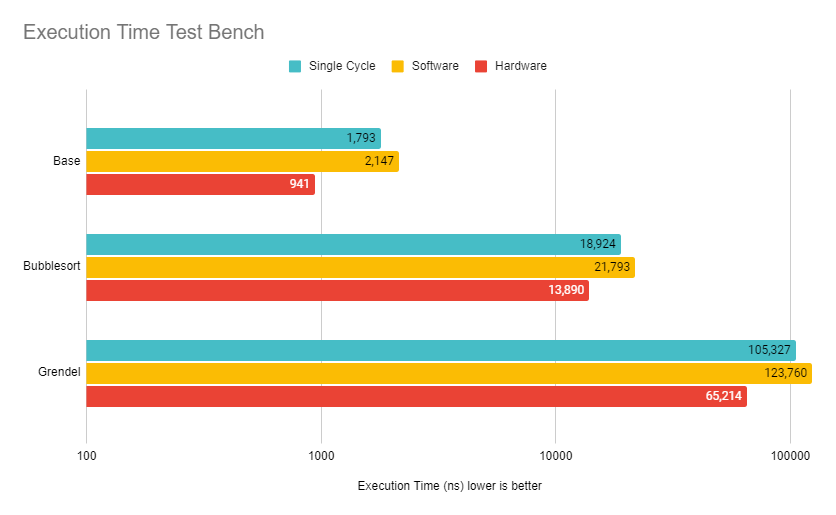

A set of test benches were compiled to analyze the performance of each of the three processor designs. Each one demonstrates a set of advantages and disadvantages that must be considered when choosing one implementation over another.

View the source code

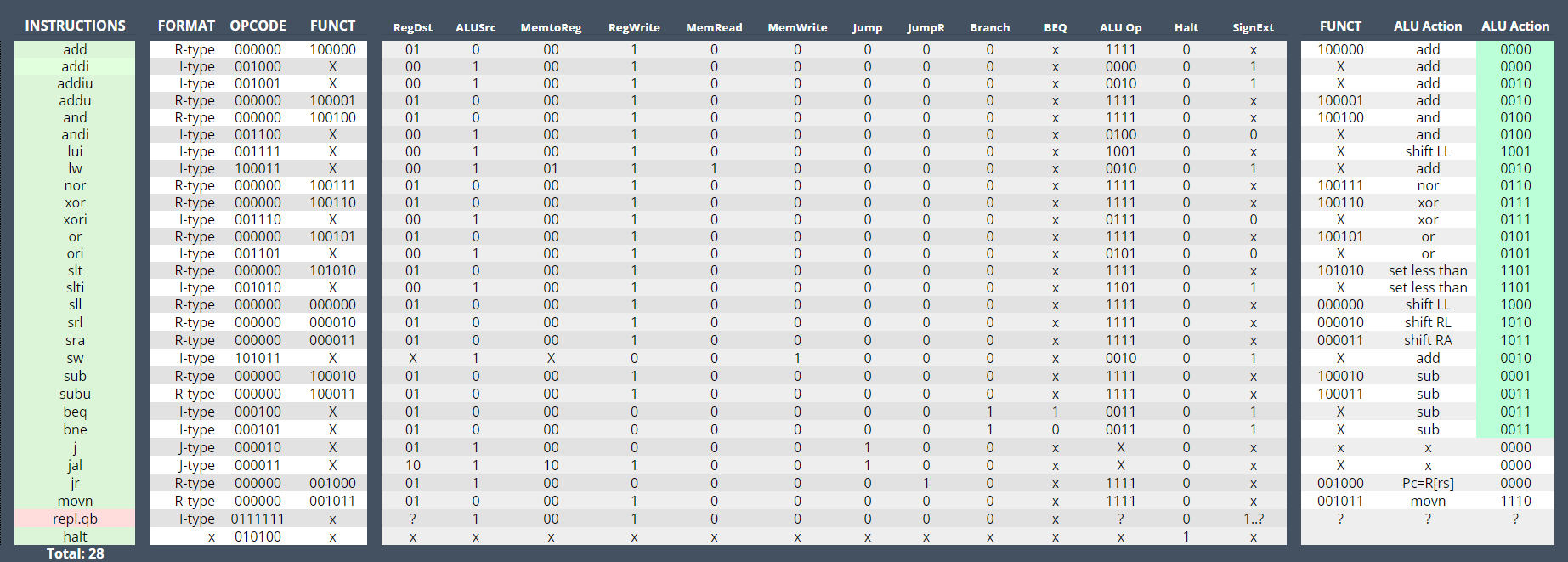

1 Instruction Set

These processors support a limited MIPS instruction set seen below.

Produce: Changes registers or memory

Consume: Accesses registers or memory

2 Control Logic

Each instruction was broken down into the required signals to operate correctly.

The fetch logic, responsible for reading the instruction memory, must support branch and jump instructions as they do not follow the consistent PC+4 that most other instructions do. These functions include: BNE, BEQ, Jal, J, JR. Each of these instructions behave differently. The Jump and Link instruction, for example, the PC+4 address must be written to the register file. The Jump Register needs to read an address from the register file into the fetch logic path.

3 Single Cycle Processor

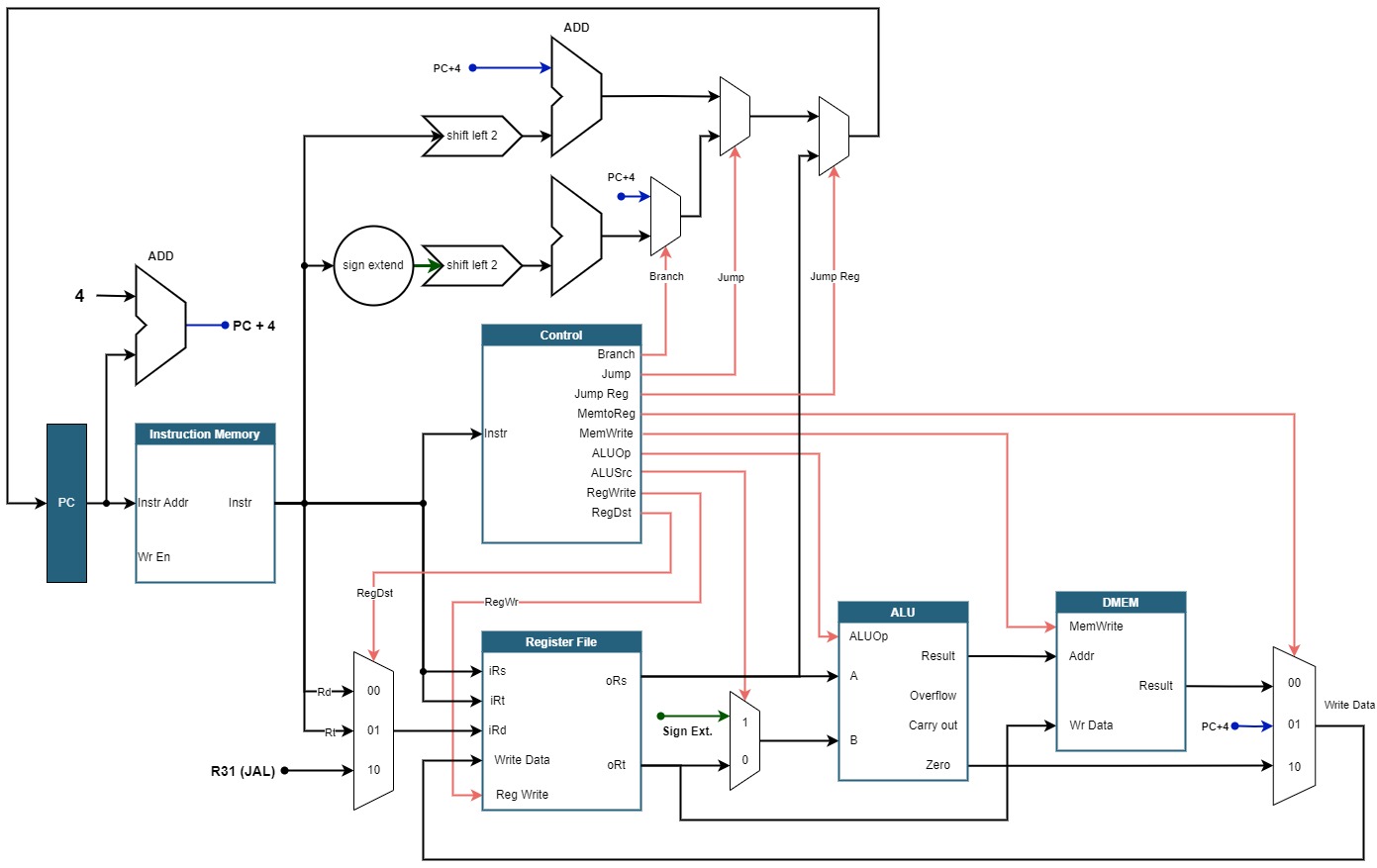

3.1 Design

This processor is a single-cycle design that aims to perform one instruction in a single cycle of the CPU. There are several advantages and disadvantages of a design like this. The design is rather straightforward, but because the cycle time is fixed to the slowest instruction, faster instructions cannot execute more quickly.

3.1.1 Design Diagram

The top-most portion of this diagram is the fetch logic, which accounts for the branch and jump instructions described in Control Logic. In future iterations, the fetch logic is placed in its own submodule.

3.2 Benchmarks

As expected, the single-cycle design executes each test in the same amount of cycles as there are instructions, resulting in a CPI of one. The cycle time however showcases that the critical path of the processor is 49.80ns.

| Test | # Instructions | # Cycles | Cycles Per Instruction | Cycle Time | Execution Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | 36 | 36 | 1.00 | 49.80 | 1,793 |

| Bubblesort | 380 | 380 | 1.00 | 49.80 | 18,924 |

| Grendel | 2,115 | 2,114 | 1.00 | 49.80 | 105,327 |

| ns | ns |

3.3 HW Optimization

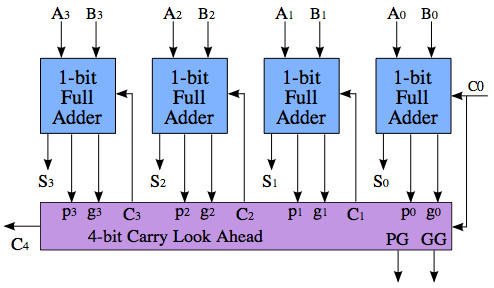

Since the CPI can’t be improved, other factors have to be considered for optimization. In particular, the cycle time is limited by the critical path of the processor. The critical path of this processor is through the ALU. Since the processor’s cycle time is bound to the latency of the critical path, optimizing the ALU would directly improve the performance.

In its current form, the ALU uses a simple ripple carry adder that is the slowest component outside of memory access. The latency comes from the propagation delay of the carry bits, as one adder can’t compute until the previous adder’s carry bit is produced.

A carry-lookahead adder solves this problem by computing whether a carry will be generated before it actually computes the sum. Below is an example of one design, although the benefits are only seen for larger computations. This would significantly decrease the latency of the ALU and improve the critical path of the processor. A lookahead adder would significantly decrease the latency of the ALU and improve the critical path of the processor, but would increase the area and power required.

4 Software Scheduled Pipeline Processor

4.1 Design

The software scheduled pipeline processor design naively implements a pipeline design without any hazard mitigation. The pipeline features five stages: Instruction Fetch, Instruction Decode, Execute, Memory, and Write Back.

The design diagram is largely identical to the hardware scheduled pipeline processor, but the hazard mitigation is done in software rather than hardware.

4.2 Benchmarks

| Test | # Instructions | # Cycles | Cycles Per Instruction | Cycle Time | Execution Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | 111 | 120 | 1.08 | 17.91 | 2,147 |

| Bubblesort | 936 | 1213 | 1.30 | 17.91 | 21,793 |

| Grendel | 5,957 | 6,937 | 1.16 | 17.91 | 123,760 |

| ns | ns |

As expected, the number of instructions are increased because hazard mitigation has to be completed in software using nops. Because of the pipelined design, however, the CPI manages to stay relatively close to 1.0. The cycle time is also improved due to the critical path only being between two pipeline registers rather than end-to-end.

The downside becomes apparent when looking at the total execution time. Despite the CPI being close to 1.0, the number of instructions and cycles have increased significantly compared to the reduction in cycle time. This results in an execution time comparable to the single-cycle design.

4.3 HW Optimization

The critical path of this processor design is the execution stage, which includes the ALU. Similar to the previous design, a carry lookahead adder would improve the performance of the ALU thus decreasing the cycle time. Other logic in this stage can be moved to adjacent stages where possible as well.

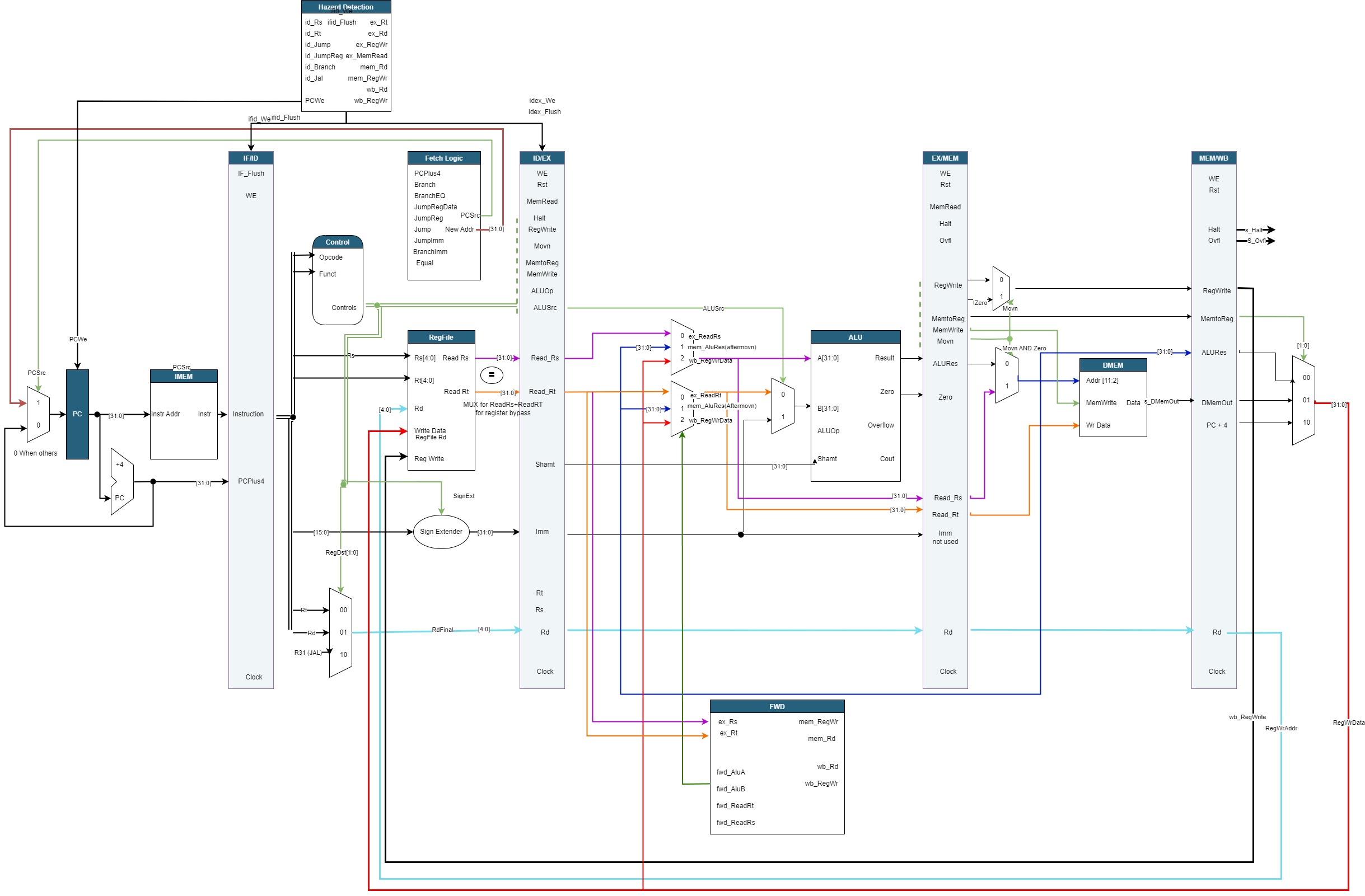

5 Hardware Scheduled Pipeline Processor

5.1 Design

The hardware scheduled pipeline processor features the same 5 stages as the software scheduled variant with the addition of hazard mitigation techniques. The purpose of automatic stalling and forwarding improves the performance of the processor by decreasing the number of wasted cycles that the software-scheduled has.

5.1.1 Design Diagram

5.1.2 Data Hazard Avoidance

The diagram above depicts five data hazards that can ocurr in the design. Four can be forwarded, and three must trigger a single stall.

The ability to detect control hazards was implemented into the forwarding logic, so no true stalls need to occur.

5.1.3 Control Hazard Avoidance

| Instruction | Stage of PC Update | Stall/Flush |

|---|---|---|

| beq | ID | Flush IFID stage, continue ID as normal |

| bne | ID | Flush IFID stage, continue ID as normal |

| jump | ID | Flush IFID stage, continue ID as normal |

| jal | ID | Flush IFID stage, continue ID as normal |

| jr | ID | Flush IFID stage, continue ID as normal |

All the branch and jump instructions have the potential to cause a control flow hazard. However, the forwarding logic correctly forwards in the event of a control flow hazard. The processor only needs to stall a single pipeline stage and can continue as normal. Implementations that lack this feature may need to stall multiple times or multiple stages.

5.2 Benchmarks

| Test | # Instructions | # Cycles | Cycles Per Instruction | Cycle Time | Execution Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | 36 | 46 | 1.28 | 20.42 | 941 |

| Bubblesort | 380 | 682 | 1.79 | 20.42 | 13,890 |

| Grendel | 2,115 | 3,191 | 1.51 | 20.42 | 65,214 |

| ns | ns |

To no surprise, the hardware-scheduled pipeline processor performed great. While the CPI suffered slightly, the number of instructions and cycles are low. This results in a significantly lower execution time compared to the other two designs.

5.3 Hardware Optimization

There is one optimization that would be relatively simple to implement and provide a nice subtle increase to control flow instruction performance. In the current implementation, all branch and jump register instructions stall their dependencies out of the pipeline. This is because there aren’t any forwarding paths set up to go into the instruction decode stage where the new control flow address is calculated.

All that’s needed to complete this optimization is to insert two muxes to the outputs of the register file before moving into the address calculation. They would have inputs of the register file and the write data values from the execute stage, memory stage, and writeback stage. Additionally, a few extra lines of logic would be required in the forwarding unit to detect the dependencies in the pipeline.

Of the 66 total branch instructions executed in the bubble sort test bench, it can be safely assumed that the majority of them are dependent on an instruction preceding it. Following that assumption, the processor would experience a maximum 200 clock cycle decrease and 40% execution time speedup in the bubble sort test bench. More modest expectations would still result in an almost 25% increase in performance. Although this hardware optimization seems trivial, the performance gain in control flow instruction heavy test benches would be clear.

6 Analysis

6.1 Execution Times

The hardware scheduled pipeline, as mentioned earlier, shows great performance gains over the other two designs. Compared to the single cycle design, it pulls a 30-60% increase in speed among our three test benches. The relatively low instruction count, CPI, and cycle time all contribute to this performance improvement.

While the average CPI might be higher than the other two processor designs, it is made up for by having a faster cycle time than the single cycle design and fewer instructions than the software scheduled design.

6.2 Branch Sequence Test

| Test | # Instr | # Cycles | CPI | Cycle Time | Execution Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SingleCycle | 41 | 40 | 0.98 | 49.80 | 2,001 |

| Hardware | 41 | 120 | 2.93 | 20.42 | 2,453 |

| ns | ns |

In all of our test benches, the hardware pipeline outperformed the single cycle design. However, there is a very specific sequence of instructions that can result in the opposite result. On the single cycle design, a branch or jump register instruction that is dependent on the immediately preceding instruction has a CPI of one. On the other hand, the hardware scheduled pipeline design must stall the dependency out of the pipeline for up to three cycles, and it must flush the instruction following the branch. This results in a CPI of three. The test result above confirms this.

7 Conclusion

In conclusion, this project consisted developing three MIPS processors: a single-cycle processor, a software-scheduled pipeline processor, and a hardware-scheduled pipeline processor. Base diagrams, control speadsheets, and VHDL code were completed for each processor. Thorough testing was completed to evaluate the performance of each design, identifying their respective advantages and disadvantages for making informed decisions in computer architecture design.